Tiny feet scamper across my cheek, up the bridge of

my nose, and over my forehead. For a moment, I think I must be dreaming, but

the sensation of something nibbling upon my hair is much too real.

I sit up and swat at my head, dislodging the plump

mouse from my tresses. With a squeak of dismay, the mouse scurries off to

burrow into a clump of straw near the oaken door.

I regret swatting at my head almost as much as I

regret sitting up so quickly. It seems as though an army of elves is playing

drums inside my skull. I touch the place where the pain is most fierce, finding

a bump the size of an egg.

Did I hit my head? Did someone else hit my head?

What is this place, anyway?

I look at about the room, turning my head slowly so

as not to cause the elves to drum harder. The walls are made of heavy stone

blocks, roughly hewn. High in the far wall, several little slits let in a few

sunbeams. There is a bucket in one corner and a neatly folded, filthy blanket

in the opposite corner. The floor is strewn with ancient, graying bits of

straw, thin in some places and mounded up in others.

In spite of my aching head, I go to the imposing wooden

door and knock. “Hello? Is anyone there?”

“Do shut up,” says a pile of straw not three feet

from where I stand. The head of an old

woman pushes out of the pile. “Ain’t never been in jail before, has you, ducks?

Ain’t nobody goin’ to bring yer tea, so yer might as well shut yer mouth.”

“Jail?”

“Stupid and silly she be, silly and stupid is she,”

the woman sings. And then she buries herself in the straw again, cursing and

groaning all the while.

“Jail,” I say again, to myself. “How did I end up in

jail?”

I begin to walk, to pace the perimeter of the room.

Ten steps, then turn. Twelve steps, turn. Don’t step on the old woman—and don’t

breathe near her either. Her stench is somewhere between dunghill and rotten

onion, with a dash of sour beer.

Something brushes against my thigh. I reach into the

deep pocket of my skirt and pull out a small vial, a key, a silver coin, a

little scroll tied with a blue ribbon, and a signet ring. Such treasures and

mysteries!

The old woman begins to snore and I find a place as

far from her as possible to sit upon the floor. I place the treasures in my

lap, fingering one after the other, willing myself to recall their meanings and

origins.

I hold the key in my right palm and the coin in my

left and close my eyes.

I remember

turning the key in the lock, the click of the mechanism as it yielded, and the

way the door swung open with a whisper—on well-oiled hinges. Hinges befitting

the door of a prince’s chambers.

I remember—it seems

to me that it must have been just minutes before

opening the chamber door—bribing the guard at the kitchen door at the stroke of

midnight, giving him the silver coin, so that he would let me into the palace.

I remember speaking the code word to him which made his eyes grow wide and

caused him to press the key into my hand—and to return the coin I had just

given him.

I set the key and coin in my lap and pick up the

vial. I pull the cork from its mouth. Holding it to my nose, I inhale a

medicinal scent. And I remember seeing

the prince in his bed. How pale he was! His lips as blue as pansies, his closed

eyelids the same. His breaths scraped in and out of him like shards of glass

instead of air. Beside him, the queen dozed, chin on chest, her jeweled crown

all crooked.

He opened his

eyes and smiled at me before I dared whisper his name.

“You have come,” he

said. His voice was barely a voice at all, more like a tiny wind. With great

effort, he placed one of his hands on the other and slipped the signet ring

from his slim finger. “Here,” he said. “It is not the wedding ring I would have

given you, but it is all I have to give now. All I can give you before I leave

this life.”

With trembling

hand, he reached out and slid the ring onto my finger. And he smiled. In spite

of his wretched state, I had never seen anyone more beautiful.

“My prince,” I

whispered. “I have brought you this.” I held forth the little vial. “It will

make you well again. I am sure of it.”

He shut his

eyes again and let his head sink deep into his snow-white pillow. “Beautiful

girl,” he said. “Remember how we met? Just before I took ill three years ago. Beside

the river. You in your dove-grey convent robes, serious as the plague?”

“Orphans wear

what they are given,” I said. “Now drink this down before the queen awakens and

casts me out.”

He swallowed

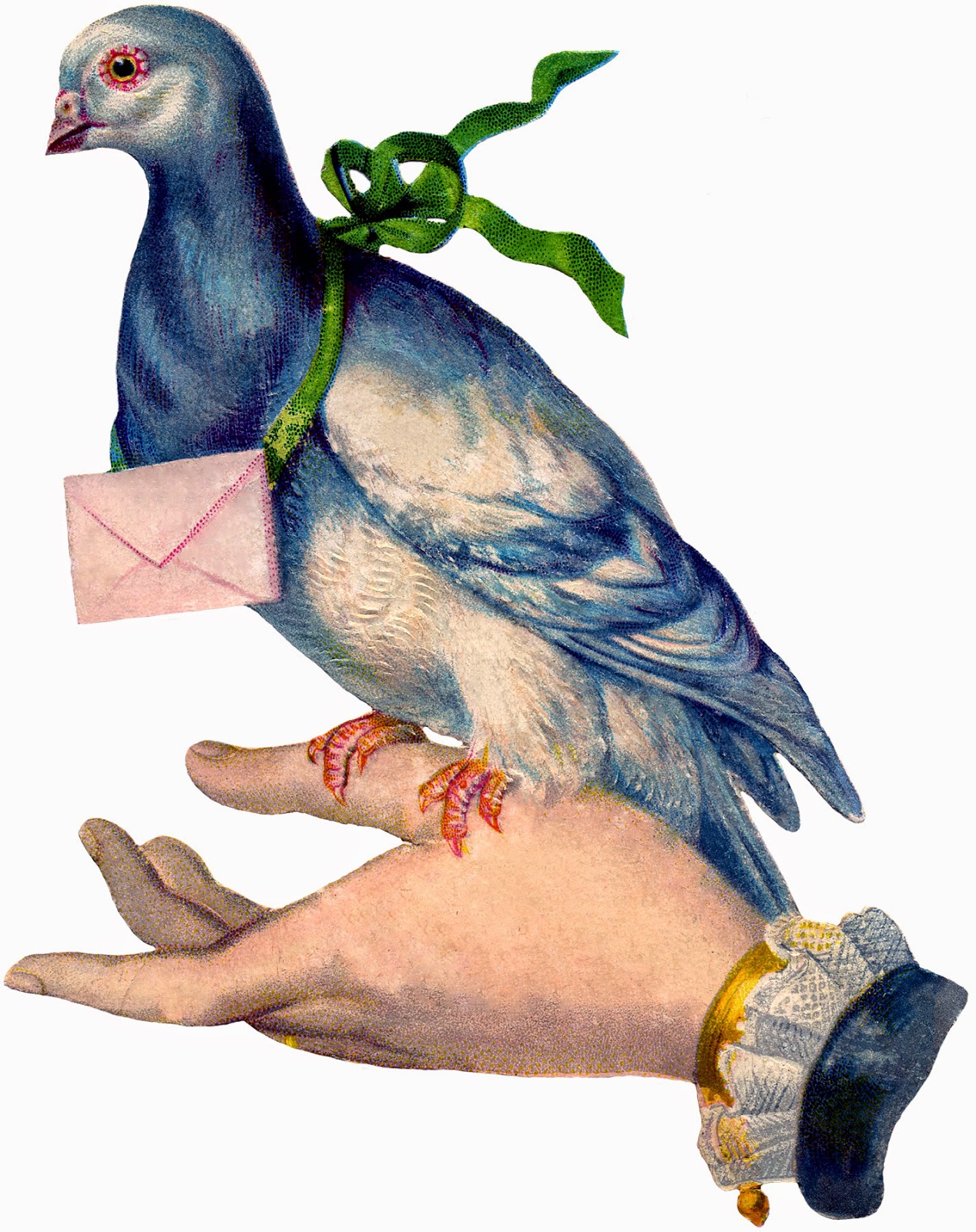

the medicine, grimacing at its bitterness. And then he sighed. “There is one

last letter for you,” he said. “In the drawer there. I had not the strength to

tie it to the pigeon’s leg. But I did want to say goodbye to you. Your letters

have kept me alive longer than anything the physicians could have dosed me

with.”

“We both have

the pigeon to thank for our happiness,” I said. Inside the drawer, I found the

little scroll. I slipped it into my pocket, and the ring fell in with it, just

as the queen awoke with a start.

“Guards!” the

queen shouted. “Trespasser! Remove this dirty peasant from the prince’s

chambers!

“No!” the

prince shouted with the force and authority of the healthiest of kings.

A guard lunged

for me and I tripped. I must have fallen and hit my head on the bedframe or

stone floor.

Only to awaken here, in this grim cell.

Is my dear

prince still alive?

I wonder. Did the medicine work? Will I

ever see him again?

The ribbon slips from the scroll easily, and I

unroll the square of parchment. I read aloud, my heart aching with the thought

of losing the one I love best.

“Darling One, I

know how you searched the wide world to find the cure for my disease, and I am more than grateful. How

I wish you had not done so in vain! For I shall not see you again in this

world-”

The door swings open with a deafening creak. I

stand, and all the treasures scatter among the straw.

But I need no other treasure than the prince who

stands before me, bright with health and love.

“Come,” he says. “A jail is no place for the bride

of a prince.”

(With thanks to the Kingdom Writers for the story prompt & their invaluable support!)

Comments

Post a Comment